La pasta di Giovanni Fabbri: pasta-makers since 1893

Pasta Fabbri has two secrets: using good wheat and slow processing operations because pasta can only be truly tasty when it is slowly bronze-died and dried

Toscana & Chianti News n°7 – September 2011

Article in English :

“Giovanni Fabbri’s pasta has already celebrated its first century of life; in fact, the factory located in Strada in Chianti has been producing pasta since 1893, which amounts to almost four generations. This year also marks the recurrence of a special centenary: that of the electrical pasta factory. It is interesting to discern, wedged between the old certificates and contracts, the yellowing hygiene authorization which promoted the establishment to hygienic pasta factory status and replaced the horse with electricity. It is of course an achievement that Giovanni Fabbri is proud of, although he remains, at heart, a man tied to tradition.

Upon entering the pasta factory, you find yourselves, quite surprisingly, in a sort of tactile museum, where Giovanni still uses old objects such as presses, small presses and machines to pull the dough, i.e. the Pastamatics of the early 20thcentury.

It is not uncommon to see Giovanni launch into an explanation of how spaghettoni (thick spaghetti) or sedanini (elongated, narrow, ridged tubes) are made, starting from the introduction of the wheat grains into the stone mill grinder (to produce flour), which, thanks to a system of sieves, determines the flour’s texture and purity.

Giovanni Fabbri’s heart opens up when he talks about removing the wheat bran to produce semi-wholewheat flour- which is of the refined variety for bread and of types 1 or 2 for pasta. Using a normal type of flour causes the loss of all the fibres; however, thanks to the dedication of Giovanni Fabbri and his friend Renzo Marinai, a vine-dresser from Panzano, who has resumed the trade of cultivating ancient wheat, the fibre in the pasta remains one of its distinctive elements. In the Conca d’oro (Golden Valley) in Panzano in Chanti, amid the olive trees, every year small allotments are sown with Grano Cappelli wheat. The latter is a native wheat that was slowly being forgotten, but that has luckily experienced a comeback, providing nourishment and elasticity to pasta.

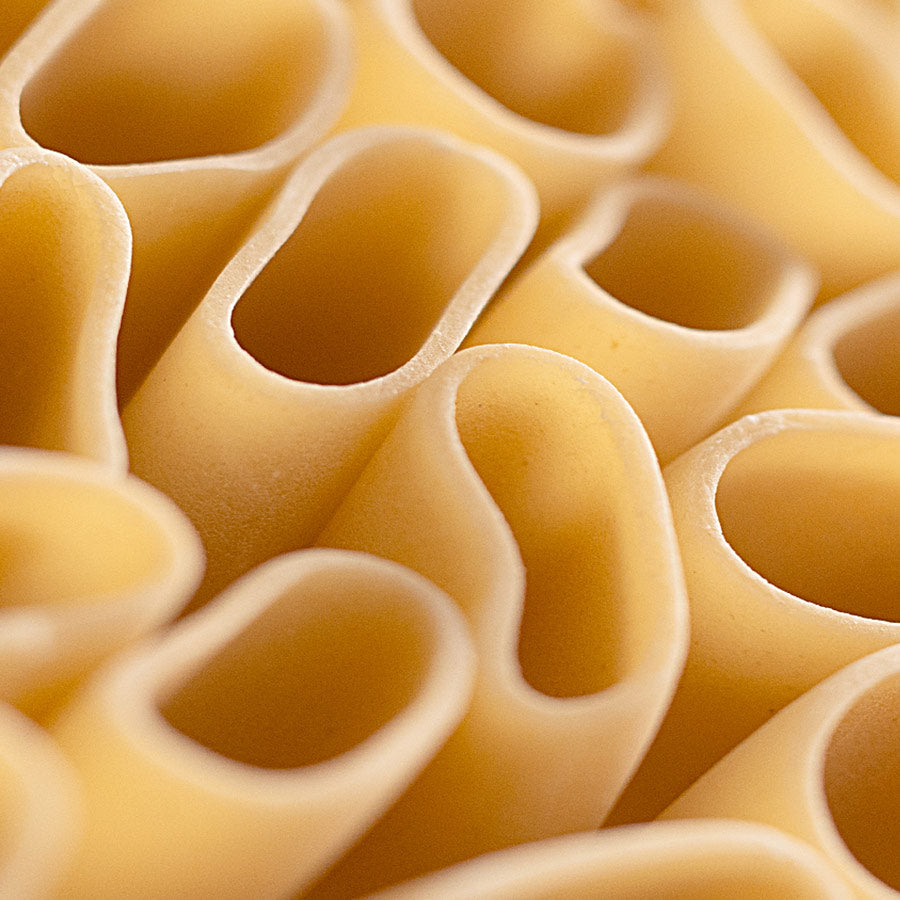

Pasta Fabbri has two secrets: using good wheat (such as the white or black monococco, also known as the spelt of the Romans and possessing an extremely thin ear, Cappelli wheat, with gold-coloured ears and long “black bristles”, or modern quality wheat), and slow processing operations because pasta can only be truly tasty when it is slowly bronze-died and dried. Gluten elasticity is the yardstick to measure optimal and consistently high-performance wheat. The pasta is then dried in special rooms for three to six days at a temperature below 38°C.

The resultant product is high-quality pasta representing the great Tuscan tradition as its best.

Pasta Fabbri.”

Trascrizione dell’articolo in italiano:

“La Pasta di Giovanni fabbri ha già festeggiato il suo secolo di vita: nello stabilimento di Strada in Chianti, infatti, si produce pasta dal 1893, ovvero da quasi 4 generazioni. Anche quest’anno ricorre un centenario speciale, quello del “pastificio elettrico”. È bello vedere tra le vecchie bolle e i vecchi contratti l’autorizzazione igienica di allora che dava il nulla osta a diventare “pastificio igienico”, eliminando il cavallo e introducendo l’energia elettrica.

Ma questo è solo un piccolo vanto “ tecnologico” di cui, oggi Giovanni Fabbri, va fiero, perché lui fondamentalmente è legato alla tradizione.

Quando si entra nel pastificio ci si trova, con grande sorpresa, in una specie di “museo toccabile”, dove i vecchi oggetti, vengono ancora utilizzati da Giovanni: torchi, torchietti, le macchine per tirare la pasta, ovvero le “pastamatic” dei primi del Novecento.

E’ facile vederlo spiegare come nasce uno spaghettone o un sedanino, partendo proprio dalla macina a pietra, dove mette i chicchi di grano, e dalla quale esce la farina, che grazie a un sistema di setacci ne determina la consistenza e la purezza.

A Giovanni Fabbri si apre il cuore quando parla di togliere la crusca per fare una farina semintegrale, che è di tipo semolato per il pane e farina tipo 1 oppure tipo 2. Utilizzare una farina normale comporterebbe perdere tutte le fibre; ma grazie all’impegno di Giovanni Fabbri e dell’amico Renzo Marinai, vignaiolo di Panzano, che è tornato a coltivare l’antico grano, la fibra nella pasta continua a essere uno degli elementi caratteristici della sua pasta. Nella “Conca d’oro” a Panzano in Chianti, tra gli olivi, vengono seminati ogni anno piccoli appezzamenti di “Grano Cappelli”, un grano autoctono che piano piano si stava dimenticando, ma che per fortuna è tornato a farsi valere, regalando nutrimento e elasticità alla pasta.

I segreti della pasta Fabbri sono due: lavorare un buon grano, come il bianco o nero “monococco”, detto anche “farro dei romani”, con una spiga finissima o il “Cappelli”, con spighe oro e lunghi “baffi neri” o ancora il grano moderno di qualità, e la lavorazione lenta, perché è da una lenta trafilazione in bronzo e da una lunga essiccatura che la pasta diventa buona. Il grano per essere consistente e ottimale deve produrre un glutine elastico.

La pasta poi viene essiccata in apposite “stanze” ad una temperatura inferiore a 38°, da tre a sei giorni.

Dopo tutte queste accortezze si ha una pasta di ottima fattura, ruvida e ricca della grande tradizione toscana. La pasta Fabbri.“