Ritratto di Giovanni Fabbri nel libro “Beaneaters & bread soup”

Ritratto di Giovanni Fabbri, Artigiano Pastaio nel cuore del Chianti

Estratto dal libro “Beaneaters&bread soup: portraits and recipes from Tuscany” di De Mori L. / Lowe J., Quadrille Publishing, London, 2007, (Scaricare Qui l’estratto originale) :

“GIOVANNI FABBRI – Artisan Pasta Maker

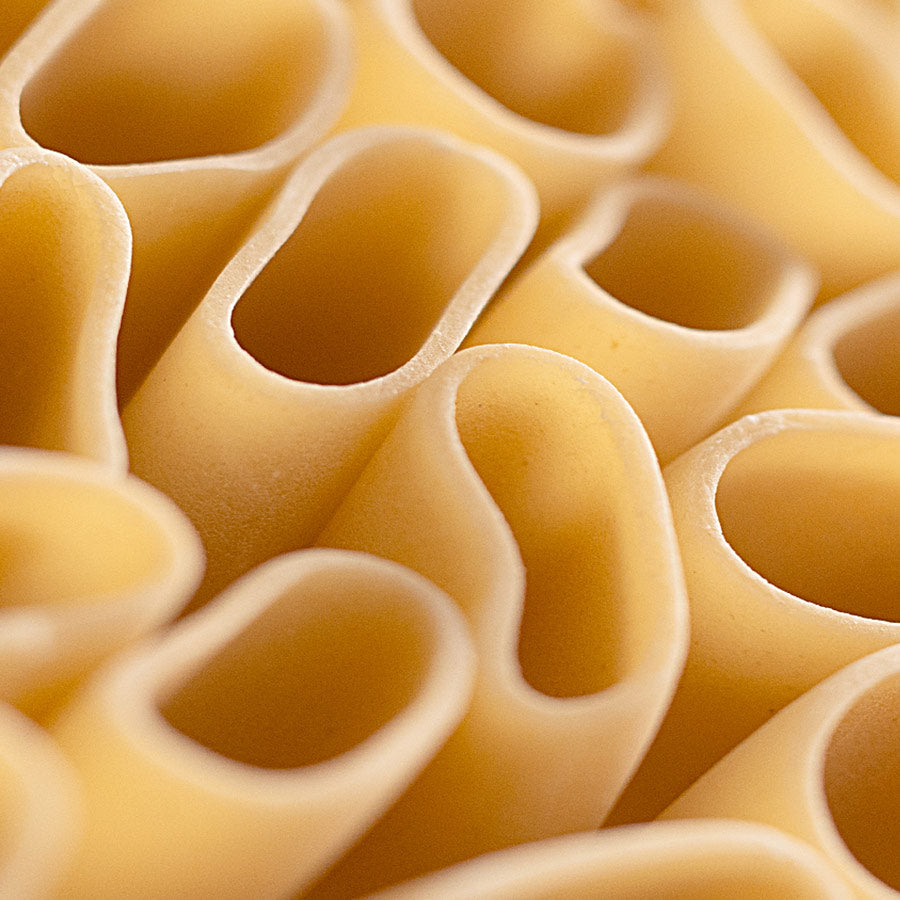

‘Did you know that San Lorenzo is the patron saint of pasta makers?’ asks Giovanni Fabbri, pulling a lever on a hulking green pasta machine. After some rumbling and groaning, the machine dutifully begins pushing ribbons of Pappardelle di San Lorenzo out of its yawning mouth. The edges are straight on one side and ruffled on the other. The straw yellow pasta takes its name from the patron saint’s feast day in renaissance Florence, an occasion when pastai in the city’s San Lorenzo quarter decorated their shops with the long pale noodles and the church broke them up into broth to offer to the poor.

We walk into a small room beside the pasta machine where rows of heavy bronze trafile (dies) patterned with the designs for scores of pasta shapes are stored. ‘This is the patrimonio of the pastificio,’ Giovanni says proudly. Some of the dies are as old as the place itself, which was first opened as bakery, pastificio and grocery store by his great, great grandfather in 1893. The main square of a small rural town in the heart of Tuscan wine country seems a strange place for a pasta factory, even an artisan one. Giovanni disagrees. ‘A hundred years ago the countryside around here was covered in wheat fields, ‘he esplains. Over the last 50 years, olives and wine grapes have mostly replaced grano and redefined the local landscape and economy, though the pastificio still buys Tuscan wheat grown around Siena, Grosseto and Pisa. A lot has changed since the days when Fabbri spaghetti was air-dried on racks right in the square, bought by weight and carried home wrapped in brown paper and tucked under one arm, like a baguette. The recipe remains unaltered – nothing more than semolina and water – though with the arrival of electricity in the early 1900’s, the Fabbri’s horse and millstones were retired. From then on, the dough was worked by machine and the pasta slow dried in heated cupboards inside the pastificio.

If the difference between fresh and dried pasta is obvious, the one between artisan and industrially made dried pasta is huge. ‘Two things make our pasta better than the industrially manufactured variety,’ says Giovanni: ‘Its texture and the temperature at which it is produced’. ‘Senti. E’ ruvido’, he says, opening the door of a drying cupboard and running his fingers through the long strands of spaghetti looped over metal rods to dry. The pasta looks smooth but is in fact slightly rough to the touch – a result of the dough’s slow movement through the bronze dies. This texture enables the pasta to hold its sauce better than smooth, slippery industrially made pasta. Giovanni is even more adamant about the importance of production temperature. ‘We want to conserve everything that nature has given us in the grain,’ he explains. If at any time during its production, the temperature exceeds 38°C, the glutens are altered, and the pasta’s ability to absorb water and sauce is compromised. Pasta that’s made commercially is dried in as little as 10 hours. Pasta Fabbri takes anywhere from 2 to 5 days to dry.”